how has the pandemic impacted the music industry?

Months of intermittent lockdown, mixed with emotional turmoil, has forced music fans, industry workers, and musicians alike to reevaluate their places in the music industry whilst living in a pandemic-stricken world. With change permeating every aspect of the musical sphere, a sense of loss is certainly apparent, but, with different modes of adaptation, such has revealed the resilience of the industry, even in a time of great difficulty.

To begin, settling into an era where gathering in groups, especially at concerts, is seldom acceptable has greatly affected artists’ ability to function, as playing shows had been a large part of their careers and livelihoods. For Boston band Trash Rabbit, gigs were a huge factor in helping establish the group’s identities as musicians. Historically, they had been privy to playing basements all over Boston every week, and moving on from that lifestyle proved difficult at first.

“[Performing] was really an outlet and it was just a great way to feel like this is worth it, like this is what I like to do,” explained vocalist and guitarist Mena Lemos. “Personally, I write music— the music I write for this band — with [the thought] that this is going to be performed live in mind. It's a big emphasis for me, on having great shows, and like, moshin' and all that emo weenie shit...and not doing that...it's just hard.”

Currently, the band, like many other musicians, have taken up livestream shows to relieve their performing fix, though it's not quite the same. For Seattle band Naked Giants, livestreaming has presented the chance for instrospection, though, they still question the effectiveness of the shows: "It's very different from live shows — it's much more casual and feels a bit like a rehearsal. I'm still unsure of how the energy translates virtually. We kind of just do our normal thing and play rock tunes, and I'm sure it's tough to get 'into' it from the audience's perspective without the actual atmosphere of a live show," said frontman Gianni Aiello.

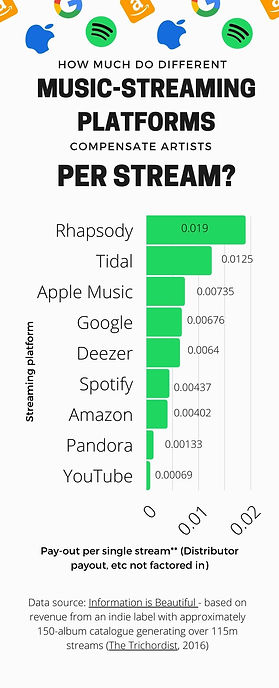

Aside from the intimacy-related barrriers presented by a lack of in-person performances, not playing shows has also presented an additional monetary threat to touring artists. Roughly 80% of most performers’ annual revenue comes from touring, and additional means of income, including pay-out from streaming platforms, barely cover the bills as it is. That said, many artists have been fighting tooth-and-nail to secure some semblance of stability and normalcy in a time of financial insecurity.

For some, livestreaming has presented the opportunity to crowdfund and reach out to their audiences so as to aid their financial woes. Some venues, as Aiello noted, have even begun to launch livestream series: "What started as Instagram live streams from basements and rehearsal spaces has grown into full productions with lights and fancy cameras and everything," he continued. "What's more, is that a majority of shows these days are community benefits — they're largely donation-based and a lot of them put money forward into either mutual aid funds for COVID or toward the Black Lives Matter movement and associated organizations."

Aside from adjusting to a world without performing, the industry has also had to adapt in terms of content creation. In a search for normalcy, some musicians have been creating (some, at a rate like never before) in a time when there isn’t much else to do while stuck inside. For many, producing new material became a distraction from their sense of uncertainty about the state of the world: “I feel like having a project to work on during the pandemic saved my life. Or at least kept me from becoming truly dead inside,” said Boston musician Brendan Wright (aka Tiberius). During quarantine, Wright cracked down on finishing his fourth LP, entitled Lull.

Additionally, the pandemic encouraged many artists to experiment with other means of writing/producing and to test the waters outside of their comfort zones, which has allowed content creation to flourish as well. For Boston artist Thetamancer, quarantine presented the opportunity to create for the very first time, especially with the lane of opportunity created by a focus on online collaboration. This led him to reach out to and work with an artist who he personally takes inspiration from LA-based creator, Slater. “I probably wouldn’t have had the opportunity to collaborate with one of my favorite artists if it weren’t for lockdown,” he explained.

"What I believe [the pandemic] has ultimately done for us is force some very important introspection on our part as to where our values lay, without the prospect of touring and focusing on the physical aspect of performing at all, we needed to understand what kind of value we have for creativity just for the sake of it. It’s turned out to be a very important kind of motivation," said Charlie Anastasis of the band Liily. They, too, have turned toward creating and going back to their roots with the abundance of time quarantine has granted. As of the summer, the band finally finished their debut album, and even have a second in the works.

Aside from the positive impact the pandemic has had on musical adaptation, however, lockdown has unfortunately had a negative impact on independent venues, many of which are currently in danger of closing due to lack of revenue and support. For example, the words “Allston is Dead” have decorated a powerbox outside the former legendary Boston rock institution, Great Scott, for the past few months, having been spray-painted there shortly after the announcement of the venue’s permanent closing earlier this year. When you look at 1222 Commonwealth Ave, the venue’s former location, today, something automatically feels off, something feels missing, and that’s because something certainly is.

Currently, you can’t find a pack of cigarette smokers, huddled on the venue’s front porch in between live sets, chatting away amidst the sound of the T intermittently screeching to a halt at the Harvard Ave Green Line stop. You can no longer hear the sound of a pulsing kick drum, or a roaring crowd, sloshing around on the beer-soaked floor. The historic Great Scott awning, weathered from years of sitting overhead, has been removed, leaving the building a shell of what it once was. For the Greater Boston community, these losses are devastating, and have led many to reflect on those small details and the many memories they gained at the iconic Allston club.

SCENES FROM 1222 COMMONWEALTH

photos by Erin Christie

Unfortunately, though, Great Scott is the very tip of the iceberg regarding the dangers independent venues are facing. In the months since the pandemic rendered the prospect of holding live events essentially impossible, independent venues that can’t afford to sustain themselves without the regular revenue supplied by concerts have been dropping like flies and the National Independent Venue Association (NIVA) reports that, without federal intervention, as many as 90% of indie music venues could disappear within the next few months. Even another Greater Boston Area gem, Somerville’s ONCE Ballroom, was not able to outlast an era without live music, and, this November, announced that they will not be reopening. Earlier in the year, they even made efforts to COVID-proof their space so as to host livestream performances for bands in the area, but those efforts, it seems, were for naught.

Elsewhere, former attendees at spots such as Arlene’s in Brooklyn, Barracuda in Austin, Boot & Saddle in Philly, and countless other venues have been forced to say goodbye far too soon. Losing such important cultural staples, countrywide, has thus sparked discussion regarding the importance of keeping truly independent home-grown venues.

Part of the benefit of independent venues, part of what makes them worth saving, is the intimacy they provide. For a fan like Mica Kendall, who appreciates the opportunity for in-person interaction with the bands she loves, venues such as Great Scott are an important resource: “My favorite show that I saw at Great Scott was The Garden in 2018. A lot of artists that I enjoy, before they get really big, they typically play at the Great Scott. After that show, the next year, they played at The Sinclair [another larger Boston venue] so, it’s kind of like the Great Scott is this special, one-time experience that’s irreversible with these big bands.”

Staff at venues are also facing setbacks as their places of work struggle to stay afloat, not only due to the lack of job security, but also because part of their everyday lives has been taken away. “I miss working shows so badly,” said Bowery Boston staffer, Grady Cardeiro. “I would kill to push road cases into an undersized freight elevator for an indifferent touring act.”

Generally speaking, independent venues are their own living, breathing live institutions, and continuing to lose them would be a massive blow to the entire music industry at large (including fans, musicians, and venue staffers), hence, why there needs to be more effort put into saving them. Thankfully, though, organizers who recognize their importance have begun crowdsourcing efforts to save independent venues such as Great Scott. Recently, an investment campaign led by Carl Lavin, Great Scott's former talent buyer, collected over $250,000 to put toward the venue's potential move to the abandoned Regina Pizza in Lower Allston.

Thus, despite challenges presenting themselves in multiple different respects throughout the music industry, it's clear that the heart of the industry remains as strong as ever, and it's going to take a lot more than a deadly virus to kill such a powerful institution.

- - -

Below, you can read a collection of different stories about how the pandemic has forced people to update their lives regarding their positions in the industry. Additionally, the zine below takes those pieces (and a few additional pieces of content) and details the narrative further. It’s clear that even in the most difficult of circumstances, the resilience of musicians, and music-lovers, is unbeatable.

Read these stories + more content in the first print issue of penny!

This issue essentially tackles the same dilemma and makes an attempt to focus on how different levels of the music industry have learned to adapt and grow during the current circumstance.

Added content: more interviews, some listicles, a Great Scott yearbook (where community members recount their favorite memories there), and more.